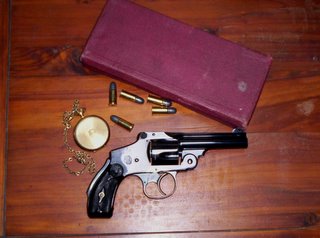

Smith & Wesson New Departure

By now we gunnies know that Governor Doyle’s veto of concealed carry in Wisconsin was sustained. Wisconsin’s citizens will have to try again next year to get concealed carry.

Doyle and his ilk forget that carrying weapons, often openly, is an American tradition. Our not too distant ancestors carried Colt Vest Pocket pistols, small imported pistols, and a variety of American and foreign made revolvers.

Men and women pocketed these guns as routinely as putting on shoes. They recognized that they were responsible for their own defense. (Of course, we’ve become more “civilized” and ended crime. Oh wait, I’m in the wrong dimension. In this dimension, criminals are still with us.) If you need evidence for my assertion, I’ll point to the huge numbers of concealable handguns that were made from the middle of the nineteenth century until World War II (and up to the present day for that matter). Someone bought and carried all those guns, or at least put them in a handy drawer.

Today’s “One From the Vault” features just such a gun. Smith & Wesson made their New Departure revolvers as self-defense weapons and built about 261,000 of them chambered in .38 S&W. They made about 242,000 very similar revolvers in .32 S&W. That’s over half a million of these little guns and someone was buying them. (NOTE: Don’t confuse a .38 S&W with the longer and more powerful .38 S&W Special [also known as .38 Special].)

The first New Departure revolvers were made in 1887 and the last ones rolled off the assembly line in 1940 when Smith & Wesson began making guns for the British who were already desperately fighting World War II. These guns were made for 53 years—a successful product indeed.

New Departures are small, relatively light, and reliable as a brick. They are top-break revolvers. You pull open a catch near the rear sight and pivot the cylinder and barrel assembly down. As you do so, a rod activates and pops empties out of the cylinder.

The revolvers earned a popular nickname, “lemon squeezers.” They were also called “Safety Hammerless” revolvers. The two names are descriptive. This double-action-only firearm has no visible hammer and sports a grip safety—who says revolvers don’t have safeties. You had to squeeze the gun firmly to fire it.

There’s a legend that Daniel B. Wesson, the burly company president, ordered his gunsmiths to make revolvers safer because he had read of an accident that occurred when a child wounded himself with a Smith & Wesson revolver. The legend may be apocryphal, but the gun is certainly designed with safety in mind.

First, there’s the grip safety. Second, there’s the lack of a hammer for a child to cock. Finally, the New Departure deserves this name if for no other reason than its trigger. The heavy trigger has an inordinately long travel that suddenly seems to hesitate. This hesitation allows a practiced shooter to aim carefully before finally releasing the shot. A child who tried to fire the gun would find the trigger pull daunting even if he or she could hold the grip safety closed.

My New Departure is a Fourth Model built between 1898 and 1907. New Departures went through five different models. The first three models are differentiated mainly by their break-action catches. The fourth model saw the perfection of the catch. The fifth and last model centered on design changes to make production easier and stayed the same from 1907 to 1940.

I found my revolver in a gun store sitting in its original box. I had to buy if for no other reason than to get its box. The box is in decent condition, but needs a little tender loving care. Relateively few boxes are left because too many owners tossed them away when they bought their new gun.

The gun itself is in wonderful condition. I’m not sure that it’s ever been fired. There are drag marks on the cylinder, but there is no erosion on the forcing cone and the rifling looks as sharp as when it left the factory. Someone thoughtlessly dry firing it could have made those drag marks (incidentally it’s inadvisable to dry fire these guns because the hammer sleeve can break—use a snap cap).

My gun has been well cared for overall, but there are a few places where acids in the pasteboard box spotted the finish. It’s possible that I could ameliorate these places with a piece of wood dipped in oil and a little patience, but I don’t really want to monkey around with it. The finish is otherwise great. The old gun makers knew how to create a finish so blue it’s really black and so deep it’s like looking into a pool of oil.

I haven’t shot my gun so I can’t give you a range report. Given that it may not have been fired, I’m not sure I will. It might just go on back into the vault sitting next to its box and remain a possible virgin. Still, it reminds me of a time when people were not burdened with laws and regulations that don’t work. It makes you wonder if Governor Doyle’s ancestors ever packed a New Departure.

No comments:

Post a Comment